‘Books need sunlight and air to live’

‘Books need sunlight and air to live’on Oct 15, 2019

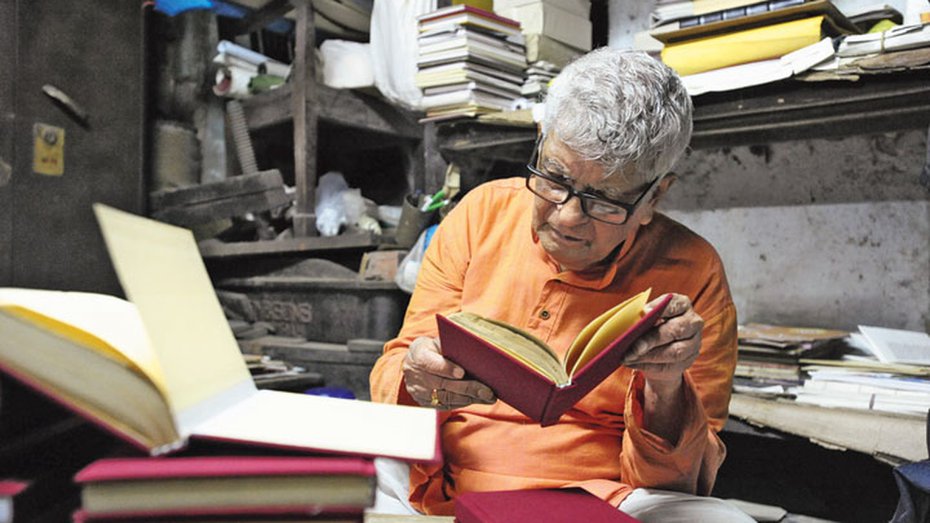

The love for books can take as many forms as the book itself. Narayan Ch. Chakraborty is living proof. The man who is regarded as one of the best binders of books in the city and is a distinguished name in publishing began his career with a brilliant sales act.

In 1961, Chakraborty, now 84, got permission from Oxford University Press, Calcutta, to sell a few damaged copies of a title by eminent historian Arnold J. Toynbee.

“The books were in all probability from the series A Study of History,” says Chakraborty. He admits to his memory failing about certain details. But otherwise his mind remains sharp as a knife.

Each book had originally cost Rs 2,200. Chakraborty bought the damaged copies at Rs 500 each and sold them at Rs 1,000 to people he knew, mostly college teachers. They were too happy to receive a Toynbee at less than half the original price. That too in instalments of Rs 100 a month. Moreover, the books they received were in excellent condition.

Because Chakraborty had worked on them. He had restored them, working with his own hands, only guided by people around him and his own instinct. That is how he became interested in the process of binding books, often a part of restoration. In the next few years, he would immerse himself in the craft of the book.

“What would you like to know?” asks Chakraborty, sitting in his small flat in Choku Khansama Lane in Sealdah. The rooms inside are full of his books — bound, and a few published by him, elegant pieces of work, sheathed in maroon handloom cloth or red leather. Some of them have discreet gold lettering.

“Even the name of this lane has so much history,” says Chakraborty, smiling, but he cannot afford to get into every detail he knows.

He was born in 1936, in Banigram, a village under Banshkhali police station in Chattagram (Chittagong in Bangladesh), very close to Burma. It was a beautiful place with three hills: “Eu, Inisi and Lena,” says Chakraborty. He names them again and again.

One of his ancestors, Kinkar Kalbhairav, was credited with changing the course of a river, but his Brahmin family of priests did not have the means to provide higher education for Chakraborty, an extremely bright boy who was naturally drawn to books.

He came to Calcutta in 1960 without completing his graduation and began to work in a College Street bookstore. The next year, he had founded his own concern, Standard Book Agency, to sell books — and publish a few. He would start DM Binding & Printing Works for the book-binding work.

He began to visit the Muslim master binders in Rajabazar to learn from them their craft. He would also restlessly look for foreign journals for the latest information and technology on binding.

“I hardly slept those days. During the day I was making and selling books. At night I was writing. I wrote the help book for the textbook Peacock Reader.” He had to earn.

He had also found a position in Calcutta at the Centre’s Chemical and Allied Products Export Promotion Council. The product he was interested in exporting, of course, was books.

Then the Centre decided that if a foreign publication was to sell more than 500 copies of a title in India, it would have to print those in India. This led to Chakraborty’s big break.

From the mid-Sixties, he was asked to do the binding work for two Indian editions of Chamber’s Twentieth Century Dictionary to be published by Allied Publishers: first of 30,000 copies, then of 20,000.

He displays a dictionary, his only copy, with pride. It is bound in maroon cloth and with gold embossing on the spine. “It’s been so many years, but the lettering shines still,” says Chakraborty. “We got the gold from a Burrabazar shop.”

“Those were busy times,” remembers Chakraborty. His workshop, in Anthony Bagan Lane, a few minutes from his residence, employed 150 men then. The next two decades would be busy, too.

He rolls off the names of his projects. He worked on a series called Wealth of India, published for CSIR Delhi by Saraswaty Press, books for Sahitya Akademi, Basu Bigyan Mandir and Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine. He had undertaken the binding of Bangiyo Shabdakosh (a lexicon of the Bengali language), in the late 1970s, but the 1978 flood destroyed about 300 copies in his workshop.

In 1972, he was nominated to the World Book Fair Committee in New Delhi, where he gave a lecture. Twice, in 1976 and 1979, he was awarded the national award for book binding and designing, by the Presidents of India.

His lectures reveal an encyclopaedic knowledge of his trade, astounding for a self-taught man who is still innocent of Google. The strength of his work, though, he suggests, does not only lie in curiosity or hard work, but also in “binding ethics”.

“I use the best board material and good quality adhesives instead of animal glue. Moisture is the enemy of books. It creates fungus,” he says.

He has never compromised on learning. Training at Rajabazar, he was fascinated by the binders’ art of painting the edges of big, bound lined exercise books (jabda khata) with wave-like designs in colour. The base used in the colouring was bile from cows.

A devout, practising Hindu, he did not shy away from the material. “It was work. Unfortunately, I did not get enough cow bile. I had to make do with goat bile.”

“I have received enough honour in life,” he says.

Another reward was the personalities he has met.

Through Nellie Sengupta, the Englishwoman who joined the Indian freedom struggle and was elected Congress president in 1933, and whom he came to know in Chittagong, he met the Bengal chief minister B.C. Roy and

Congress leader Atulya Ghosh. Both received him with affection.

In the Sixties, he had impressed P.C. Mahalanobis, the redoubtable statistician at the helm of the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), with another of his schemes. Mahalanobis asked him to sell Sankhya, the ISI journal founded along the lines of Karl Pearson’s Biometrika. Chakraborty stunned Mahalanobis by selling a significant number of Sankhya copies in Malaysia and Sri Lanka, through his contacts at the export council!

Filmmaker Satyajit Ray is another person that Chakraborty cannot stop talking about. Ray asked him to bind books from his personal collection and also recommended his name to publishers, for his book Our Films Their Films and a volume on him that was published by Basumati. In both cases, Chakraborty was the binder.

Ray wrote him a glowing certificate.

Since the death of his wife, Chakraborty lives alone in the flat. His daughter, his only child, lives in Mumbai. “She is always in touch with me,” he says.

He says he owes his work to his wife, Bijoli Chakraborty. “She was always by my side,” he says. His workshop is also lonely. Only one person works there. Currently, they are restoring a set of old books and journals for a private archive.

Chakraborty’s last big assignment was given to him by former Bengal governor Gopal Krishna Gandhi, who asked him to restore a large number of books at the Governor House library.

Age, of course, has taken its toll. “But I also cost more than others because of the quality of the materials,” says Chakraborty. He thinks that his work does not matter. “It is useless stuff,” he says, but bends intently over the book at hand.

“But remember, what books need is sunlight and air.” Books are living things.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.